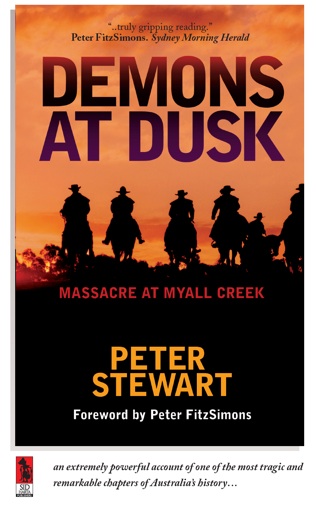

“Demons At Dusk” is a book by Peter Stewart based on the massacre at Myall Creek in 1838.

It is a story of love and courage, betrayal and tragedy, mystery and deceit and the strength of the human spirit.

“Demons At Dusk” is a book by Peter Stewart based on the massacre at Myall Creek in 1838.

It is a story of love and courage, betrayal and tragedy, mystery and deceit and the strength of the human spirit.

1838 and the British Empire is expanding relentlessly. On a remote cattle station on the frontier of the young New South Wales colony, a lonely convict hut keeper is forced to confront the power and greed which drives that expansion.

One of the convict stockmen on the station invites a group of Aborigines to the station with the promise of protection from the bands of marauding troopers and stockmen who roam the countryside.

The station’s convicts and their overseer develop close relationships with the Aborigines but the threat of violence is never far away. All must ultimately face some terrible choices – choices which reverberate across the colony and leave the young hut keeper struggling to find the courage to stand against powerful oppressors.

“… every Australian should read this book. Demons at Dusk is an

extremely powerful account of one of the most tragic and remarkable chapters of Australia’s history…reading it helped me understand my own country.”

— Peter FitzSimons. Sydney Morning Herald.

“Peter stewart’s words literally leap from the page as he carefully reconstructs he events surrounding the massacre...”

— sunshine coast weekender

“I dub this book the ‘best of 2007’ and urge every australian, black and white to read this unforgettable story”

— john morrow’s pick of the week

“the writing is engaging, often admirably spare... a graphic rendering of one of the darkest episodes in our colonial history”

— steven carroll, melbourne age

Foreword by peter fitzsimons

Like many Australians, I had vaguely heard of the “Myall Creek Massacre” but knew nothing of the detail.

That changed, however, in February 2005 when Peter Stewart, a regular reader of my weekend newspaper columns, sent me a manuscript he had written. Peter asked if I could have a “quick look” at it, with a view to writing a sentence or two which he could use for promotional purposes on the back cover.

A quick look, huh? Once, when I asked Gough Whitlam if he had read a particular book on Paul Keating he replied, “Comrade, I have glanced at it extensively . . .” and that is exactly what I intended to do on this book.

I wanted to be polite-ish, but had neither the time nor the interest to read the damn thing. That, however, is not how it worked out.

In fact, my “quick look” turned into me being drawn in from the first page, and devouring the manuscript over the next two days and nights. I finished reading it at midnight on the second night, deeply moved, and awoke with a start four hours later. Myriad sentiments were swirling within, but the most powerful was: every Australian should read this book.

I know that sounds like the mealy–mouthed thing one often reads on the back of books, but that was genuinely what I felt in those wee hours and I have firmed in my view since.

For if we are to celebrate Australia’s history in the courage and heroism Australian’s displayed at Gallipoli, Kokoda, Tobruk and Long Tan; if we are to glory in our achievements in so many fields from sport to agriculture to literature and the arts . . . then we must also remember and acknowledge Myall Creek and other stains on our national soul as a crucial part of our past.

This, too, is a part of the Australian mosaic; this, too, was a part of our journey as a people through the good, the bad and the beyond ugly to bring us to where we are today, and we cannot pretend otherwise – as much as we might like to, and mostly have to this point.

Surely, as a nation, there can be no “reconciliation” if we do not all acknowledge just what horrors we are reconciling from?

“Demons at Dusk” is an extremely powerful account of one of the most tragic and remarkable chapters of Australia’s history and makes truly gripping and valuable reading.

For me, reading it helped me to understand

my own country . . .

Peter FitzSimons

Neutral Bay,Sydney

May 1, 2007.

CHAPTER TWELVE

Sunday 10 June 1838.

George Anderson strolled out into the cool, crisp winter morning. The rain clouds having finally cleared, the sun rose into a sapphire blue sky above the gently rolling hills to the east of the station.

Anderson sauntered slowly across to the creek, bucket in hand, as part of his morning duties. As he walked, he looked toward the hut Ipeta shared with her husband, hoping she would come and join him at the creek to say her morning ‘hallo’. She normally did so on the mornings she didn’t stay with him in his hut, and although they only spent a few minutes together at such times, he felt it had recently become their special quiet time together alone, and he treasured it.

He walked in amongst the trees to the top of the creek bank, where he stood waiting patiently, looking through the trees to her hut. He only had to wait a few moments before she appeared, emerging with possum skins wrapped around her shoulders. She came to him through the dappled light of the leaf-filtered sun, the warmth from her smile enveloping him in spite of the cold morning air.

‘Good morning, Ipeta.’

‘Good morning, Jackey-Jackey.’ Her pronunciation was almost perfect. She stood before him and gave him her hand, which he took tenderly and raised to his face. She opened the palm of her hand and held his cheek briefly, before he slowly slid her hand across to his mouth.

He kissed her fingers gently, oh so gently, just as she had taught him. Their eyes – eyes that connected worlds – never broke contact. He, the convict outcast from the most powerful empire on the planet, and she, the tribeswoman of its oldest civilization. He wanted to know why she cared for him so.

‘Ipeta, you’re so good to me, so kind. Why are ya so good to

me?’ She tilted her head slightly to the side, indicating to her lover she didn’t understand. How could she? he thought.

‘Me good?’ she asked.

‘Yes, ya good; ya so very good.’ Anderson smiled. ‘But why? Why

are ya so good to me? Because we protect ya? Why?’

‘Why?’ Ipeta tilted her head again.

‘How do I explain “why”?’ the convict mumbled to himself in happy frustration. Without further prompting, though, Ipeta took his hand and pressed it against his chest. ‘Jackey-Jackey good man.’

Anderson smiled, knowing it was as much of an answer as he was ever likely to get; and as he looked into her deep brown eyes he realised it was probably the best answer he could ever get. He just hoped it was true.

While they stood there amongst the trees in the morning light, by the gently flowing waters of Myall Creek, he allowed himself to wonder if they would ever be together at a time when he was free from his convict servitude, and Ipeta free from the fear that suffocated her people’s lives. The fact that Ipeta had a husband didn’t enter his head. He stood there dreaming, savouring the cherished moments of their special time together, while twelve miles away, at Hall’s station, Death was stirring.

* * *

After a leisurely breakfast and brief chat with Kilmeister and Anderson, Foster and Mace, accompanied by Kilmeister, walked outside to saddle their horses.

‘Charlie, could you see if the blacks are ready to go?’ asked Foster.

‘Sure, Mr Foster, won’t be a moment. Davey,’ he called to the young translator, who quickly emerged from around the side of the hut and followed Kilmeister across to the Weraerai camp. They returned before Foster had finished saddling his horse.

‘Ya don’t mind takin’ a few extras with ya, do ya, Mr Foster?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, they’re scared of whitefellas, Mr Foster, and the elders are a bit worried about lettin’ just three or four of their young fellas go off by themselves with no-one to look after ’em.’

Foster was hesitant. ‘How many want to come?’

Kilmeister turned and pointed across to where the elders stood

with a group of the Weraerai men and older boys. The group in fact included most of the clan’s adult men. ‘That mob there, sir; not Daddy and Joey, but King Sandy and the others. About ten altogether.’

‘That’s too many. We don’t need that many, and I don’t propose

setting off into the bush with a mob of blacks I don’t know,’ Foster

explained.

‘They shan’t be no bother, sir. As ya seen last night, they’re a real

peaceful lot. And besides, sir, they’ve only got a couple of tomahawks to cut the bark with.’

Foster remained silent for a few moments while he finished saddling his horse. He then turned to Mace, who stood holding his mount a few metres away.

‘What do you think, Bill?’ Foster asked.

‘Well, as you say, we don’t need that many; but if Charlie thinks they’ll be all right, they shouldn’t be no trouble. They seemed friendly last night,’ Mace replied.

‘I’m not saying they’re not friendly; they are perfectly friendly. It’s just that … Oh, all right,’ Foster relented.

Kilmeister immediately waved to the Weraerai group to come over, which they did.

‘Davey, tell them it’s all right, they can all go.’

Davey passed the message on and translated the reply from King

Sandy. ‘He say tanks, Charlie, and he askem if rest of mob be all right here.’

‘Of course they’ll be all right. I’ll look after ’em,’ Kilmeister reassured them.

‘Are they ready to go?’ asked Foster.

Davey responded without hesitation. ‘Yes, dey ready.’

‘Good. Well, we’ll go, then,’ said Foster, mounting his horse.

As Foster sat astride his mount, young Charley hurried over and

pulled his trouser leg. ‘Charley come too, pleease.’

Foster looked down at the boy’s smiling face. ‘Hallo, Charley. No,

I’m sorry, young chap, you can’t; you’re too young. Maybe another time, eh?’

George Anderson stood at the door of the hut, watching as the

ten Weraerai tribesman said their goodbyes to their families. Those

leaving included King Sandy and ten-year-old Jimmy, who now said goodbye to his best friend, Johnny. It was the first time the two ten-year-olds had been separated since either of them could remember. Martha and Sandy’s friend Bobby was also going. He picked up his three-year-old daughter and held her high above his head. Holding her in one arm, he then put his other arm around his young wife and kissed the forehead of the baby son she held in her arms. As Anderson watched these tender scenes of family life, he was filled with envy.

It was mid-morning when Foster and Mace set off with their ten

Weraerai bark cutters striding along beside them. They left behind

them two old men, Daddy and Joey; two young men, Sandy and

Tommy; and thirty women, children and babies, including Ipeta,

Martha, young Charley and Johnny.

At about the same time, Fleming’s gang emerged from the stockmen’s hut at Hall’s station, armed with pistols, carbines and swords. They mounted and headed for Myall Creek.

* * *

Shortly after midday, Charles Kilmeister was out on the station

performing his daily duties with Davey and Billy, while George

Anderson remained at the hut. A shirtless Anderson was chopping

firewood, his muscles wet with sweat as he expertly wielded the axe. Young Charley stood watching him while chattering away, as was his custom. Bobby’s three-year-old daughter stood beside Charley, holding his hand and listening to every word the older boy said.

‘You good at dat, Jackey-Jackey,’ Charley observed as the axe split another piece of wood straight down the middle, ‘just like my bubba.’

‘”Bubaa”– that’s ”father”, ain’t it?’ Ipeta had been making some

progress despite Anderson’s mental inertia.

‘Dat right, Jackey-Jackey.’ The boy beamed.

‘I’m learnin’ a bit, Charley,’ the hutkeeper replied, before adding,

‘I suppose I should be getting pretty good at chopping wood by now, though. I’ve been doin’ it long enough.’ Anderson looked up from his work to see Martha and Bobby’s wife, who as always was holding her baby in her arms. The hutkeeper smiled. ‘Hallo, Martha.’

‘Hallo, Jackey-Jackey,’ said Charley’s young mother, returning

Anderson’s smile.

The children turned to their mothers, who spoke to them gently

before Charley looked back at Anderson. ‘We gotta getem sumfin’ eat. Back soon, Jackey-Jackey.’

‘Yair, I know ya will.’ Anderson grinned.

* * *

It was mid-afternoon, and George Anderson was in the hut preparing

supper for the stockmen’s imminent return. Charley and his little friend, Bobby’s daughter, sat at the table watching him again.

‘Jackey-Jackey, Midder Boss back soon?’ Charley asked.

‘Probably be a few more days. You miss Mr ’obbs, do ya, Charley?’

‘Yair, he my friend. Likem you, Jackey-Jackey.’

‘Thanks, Charley.’

‘I wish he were here,’ the boy sighed. ‘He good.’

‘Yair, he is. About the nicest overseer a convict could have, really.’

‘Convict? What dat?’

‘You still don’t understand that, do ya? Charlie, Andy and me – we’re all convicts. But I suppose you can’t understand it, because there’s nothin’ like it – like a gaol or anything – that your people ’ave.’

‘Gaol? What dat?’

* * *

Five miles to the west, Death cantered beside Myall Creek.

* * *

By late afternoon, Foster and Mace, along with their ten Weraerai bark cutters, had arrived at Dr Newton’s station, some sixteen miles due west of Dangar’s. As they approached the huts they were met by a highly anxious young lad, Johnny Murphy, who came running up to them.

‘Mr Foster, Mr Foster,’ he called as they rode up, ‘there were a big party of horsemen here yesterday, just after you left, and they had guns and swords and everything, and they were lookin’ for some blacks, and they were gonna go up to Dangar’s to get the blacks up there.’

Thomas Foster went pale. ‘What? Calm down, Johnny. Who are these men you’re talking about?’ he asked, jumping from his horse.

‘Mr Sexton says they was some of the stockmen from round the

district and a squatter was leadin’ them. Mr Sexton says his name

was John Fleming.’

Knowing Fleming’s reputation, Foster needed no more convincing.

He immediately turned to Mace. ‘We’re going to have to send this

mob back, straight away.’ He then rushed over to King Sandy and, with the help of frantic hand gestures, tried to explain the situation.

‘You must go back. There are horsemen looking to kill your mob.

Horsemen with guns. You must go back.’

Although King Sandy didn’t understand many of the words Foster was using, he quickly picked up on the urgency of the message.

Ten-year-old Jimmy then worked out what Foster was saying and

began explaining it to King Sandy. A look of sheer horror gripped

his face, and quickly spread across the faces of the other men in the group. Bobby let out an audible moan of grief and fear for his wife, his daughter and his baby son.

Realising they now understood, Foster urged them to return immediately. ‘Now, you must go back by the mountains, where they won’t find you. Stay away from the track we came down on. Go by the mountains.’

Jimmy again acted as interpreter, and the terrified group immediately set off to run the sixteen miles back to Myall Creek.

* * *

But they were already too late. Death had arrived at the top of the

ridge, half a mile to the west of the Myall Creek station huts. The

sounds of the multitude of birds which inhabited that ridge were

silenced, replaced by the snorting and stamping of excited horses as they were reigned to a halt. Silhouetted against a western sky slowly becoming the colour of fire, the demons stared down at the Weraerai camp before kicking their mounts into a gallop.

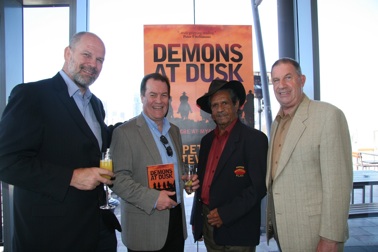

Author Peter Stewart with Peter FitzSimons, Lyall Munro - a Kamilaroi elder and Des Blake - a descendant of one of the perpetrators of the massacre.

Demons at Dusk: Massacre at Myall Creek, now available at Gleebooks. www.gleebooks.com.au